The Israeli-Canadian journalist and anti-racism activist David Sheen has posted on his website a number of letters that he found among the files on the African Hebrew Israelites at the Israel State Archives in Jerusalem. Addressed to then-Prime Minister Golda Meir, the letters were written in late 1971 and early 1972 by American Jews in response to the government’s deportation of several African Americans who had arrived from the U.S. with the intention of settling with the Hebrews in the Negev. The writers praised the government’s handling of the situation and urged Meir to prevent more black people from entering Israel. One woman, a Mrs. Melnick from Philadelphia, wrote:

Do your people realize what would happen or could happen to precious Israel if the terrible negroes [sic] would settle there? They breed like flies and stir up the most horrible crimes and I’m sure you’re aware of how animalistic they are. So please try and work hard to keep them out.

Another wrote:

Please learn from America’s mistakes. Keep the blacks out of Israel; send them back to America. We Jews don’t want Israeli cities to turn into slums nor do we want to see Israeli women raped, robbed and beaten. Blacks in America are used to living on welfare. That is why the Blacks in Israel refuse to work; they want to live on welfare in Israel. What nerve.

This letter was signed “A friend of Israel.”

The sentiments expressed in these and the other letters that Sheen posted are abhorrent, of course. They are a reflection of several phenomena: the casualness of 1970s racism, the propensity of American Jews to hold strong opinions and to share them publicly, the chutzpah of American Jews who think they know what’s best for Israel, and the cowardice of those who express vile thoughts anonymously. But the letters that Sheen posted online are not representative of the more than 25 messages that the prime minister’s office received about the Hebrews.

The State Archives also contain many letters and telegrams in support of the Hebrews’ quest to immigrate to Israel, which they believe to be their ancestral homeland. (The question of whether they were, in fact, entitled to immigrant status under the Law of Return will be addressed below.) These supporters included Dr. Ronald Sederoff and his wife, of New York City, who wrote:

As Jews who have considered immigrating to Israel, we were appalled by recent news reports that black Jews from Chicago were refused resident visas to Israel. Has Israel become a place where Jews seeking refuge are no longer welcome? Could it be that those who have suffered so much from racial prejudice now have started to promote racism in Israel itself? Would a Russian Jew with no job be refused residency in Israel?

Another supporter, “a white American Jew living in Mexico” named Daniel Sussman, wrote:

As a fellow Jew who has Israel in his heart, I beseech you to influence your government of Israel to welcome to Israel and treat with justice and kindness all who wish to worship our God and obey the laws of Israel, regardless of the color of their skins, so that we may set an example to the rest of the world.

One particularly touching letter was penned by an Israeli schoolteacher named Asher Eisenberg. In blue Hebrew script, Eisenberg wrote that “as the son of a people who spent the last two thousand years wandering and searching for a place to call home, I see myself in their position.” He also drew a parallel between the Hebrews’ plight and that of Soviet Jews stuck behind the Iron Curtain: “As the prime minster of a country that struggles to this very day to free her people from the Communist states, doesn’t the overwhelming similarity of their situation bother you?” The tone of this letter could not be more different from that of the letters that Sheen posted.

***

The Israeli government began receiving letters about the Hebrews shortly after a group of 39 arrived from Liberia on December 21, 1969 and requested entry under the Law of Return, which provides Jews with automatic citizenship and absorption assistance. They were held overnight at Lod Airport (now called Ben Gurion Airport) because, according to news reports, immigration authorities “were hesitant to accept the contention that the Americans were Jews.” Some letter writers saw the treatment of the would-be immigrants as discriminatory and warned Meir of the potential fallout of bad press. “This case can thus turn into a blessing or a curse,” wrote Alan Hauser on January 4, 1970.

Not only are the Blacks of America and many African States watching but countless liberals the world over, among them many Jews in the United States, who are engaged in a battle against Arab propaganda and in support of Israel. Let’s stop questioning their 101% ‘Jewishness.’ Let’s show the world that Israel is not discriminating, that it welcomes all Jews to their new home regardless of color.

Attached to Hauser’s letter was a carbon copy of the official response he received from the Prime Minister’s office, which read in part: “We join you in the hope that they will be fully absorbed in the country and that their settlement here will turn out a blessing.”

Hauser, like many other letter writers, took for granted that the Hebrews were Jewish, presumably because they were described in the press as “Black Jews” or “Jewish Negroes.” But, soon after the first group arrived, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel determined that most had been baptized and raised as Christians and therefore were not Jewish according to halacha (Jewish law). The Hebrews themselves objected to being identified as Jews. In August 1971, Ben Ammi Ben Israel, the community’s spiritual leader, told reporters, “We’re Hebrews, the true descendants of the Israelites, and the true inheritors of this land.” In a “manifesto” prepared in 1974 for the Organization of African Unity, the leaders further clarified their position: “It must be perfectly clear that we must not be identified as Jews or Jewish. We are not partakers of the practice of the religious doctrine of Judaism. Moreover, we are not a religious sect; neither have we returned to Jerusalem to co-habitate with the European-Jewish Community presently occupying our land.” (They no longer claim the land of Israel to be theirs exclusively.)

How, then, did they expect to be admitted to Israel under the Law of Return? Morris Lounds, Jr., who conducted the first study of the community in the late 1970s, wrote that they requested immigrant status without explicitly claiming to be Jews, thinking they “were being very clever” in doing so. But there is evidence that they did identify themselves as Jews at the airport. Hizkiyahu Blackwell, the first Hebrew to settle in Israel and the de-factor leader there before Ben Ammi arrived, was quoted in the New York Times as saying: “We are Jewish. We have always been Jewish, and we have come to Israel for the same reason any Jew comes here.” (Blackwell, today a community “prince” known as Nasik Hizkiyahu, told me in an interview that he does not remember identifying his brethren as Jews or, as Israel J. Gerber claims in his book The Heritage Seekers: Black Jews in Search of Identity, as Falashas.) Lounds wonders if the Hebrews genuinely thought of themselves as Black Jews when they landed in Israel and only later embraced the Hebrew Israelite label and identity—an identity that is, fundamentally, a response to and rejection of mainstream, Ashkenazi Jewish hegemony.

Whatever the case may be, the 39 Hebrews who arrived in December 1969 received three-month tourist visas, as well as apartments in Dimona and Arad and permission to work—an unusual, half-way absorption that reflected the government’s uncertainty over what to do with them. By March 6, 1970, when Ben Ammi arrived with 48 others, the government was no longer providing the Hebrews with housing or work permits. They were now being processed as regular tourists.

***

This brings us to the question of whether the government acted appropriately in deporting 21 Hebrews—a family of three, the Richardsons, and a group of 18—who arrived on two separate flights at the beginning of October 1971.

At that time, there were approximately 300 Hebrews living in 12 apartments in Dimona; there were also perhaps a dozen families in Arad and Mitzpe Ramon. The Jerusalem Post reported that the overcrowding—20 or more people in a two-bedroom apartment, with many forced to sleep in the bomb shelters of the apartment buildings—had “aroused the ire of Dimona residents.” In response to complaints from the city’s mayor and local council, the Interior Ministry stopped renewing the Hebrews’ three-month tourist visas, which meant that most of them were now in the country illegally and could be deported. In August, several Hebrew men tried to build houses on state-owned land near Kibbutz Beit Kama; the government ordered them to stop. Later that month, during a press conference outside Zion Gate in Jerusalem, Ben Ammi accused European Jews of usurping the land of Israel and threatened to call forth “plagues tenfold and a thousandfold” if his people—“the true descendants of the Israelites”—were not given residency, housing and jobs. Then in September, the beleaguered community staged a protest at a Dimona grocery store to draw attention to their precarious economic situation. They filled shopping carts with food and attempted to walk out without paying but were stopped by the police.

So this was the situation in late 1971: several hundred African Americans, who, by their own admission, were not Jews by religion and thus ineligible to receive Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return, had overstayed their tourist visas, tried to squat on state land and steal food, and made vague threats against the government. There was even speculation that the influx of Hebrews represented “an act of provocation by elements hostile to the state.” (This rumor was unfounded, though an Egyptian politician who was aware of the Hebrews’ predicament did invite them to settle in his country, then an enemy of Israel.) Against this backdrop, the government’s decision to prevent more Hebrews from entering the country and settling down with their struggling brothers and sisters in Dimona, appears to have been justified. But, given the racial dimension of the whole affair, it was not easily digestible. Put another way, it was easily spun by the media-savvy Hebrews and their allies in the African American community as evidence of discrimination by a racist Israeli government.

A few days after the 21 were deported, the Hebrews denounced the government in a press release issued from Dimona. “How can the Israeli government have the audacity to refuse entry of these people into Israel except because of racism?” they asked. “What else could be the problem but the upsetting of a Nazi-style super race society by the appearance of these people?” (They certainly did not help their cause by using such loaded language.) Back in the U.S., Rudolph R. Windsor, a Hebrew Israelite leader and author of an influential book about African Jews, called a press conference in Philadelphia to address the situation in Israel. He said:

Once again, we have a situation where a few white men, in this case the Orthodox rabbis of Israel, have separated and discriminated against black people, in this case Black Israelites, because of the color of their skins, and denied us equal treatment in our desire to return to our ancestral homeland. Many white Jews have settled in Israel over the years without documented evidence of their being Jewish for reasons beyond their control.

Windsor argued that Hebrew Israelites should not be expected to produce such evidence if European Jews and Soviet Jews were not required to do so up to that point. Neither could they, he wrote, since their ancestors were “forced by their slave masters to live as Gentiles.” He concluded:

It is one of the tragedies of our modern world that these Black Israelites, these descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, are once again treated as aliens in their own land. Incidents like these can only sully and demean the good name of Israel and divide the Jewish people. We urge that every fair-minded person, white and black, Gentile and Jew, speak out against this injustice.

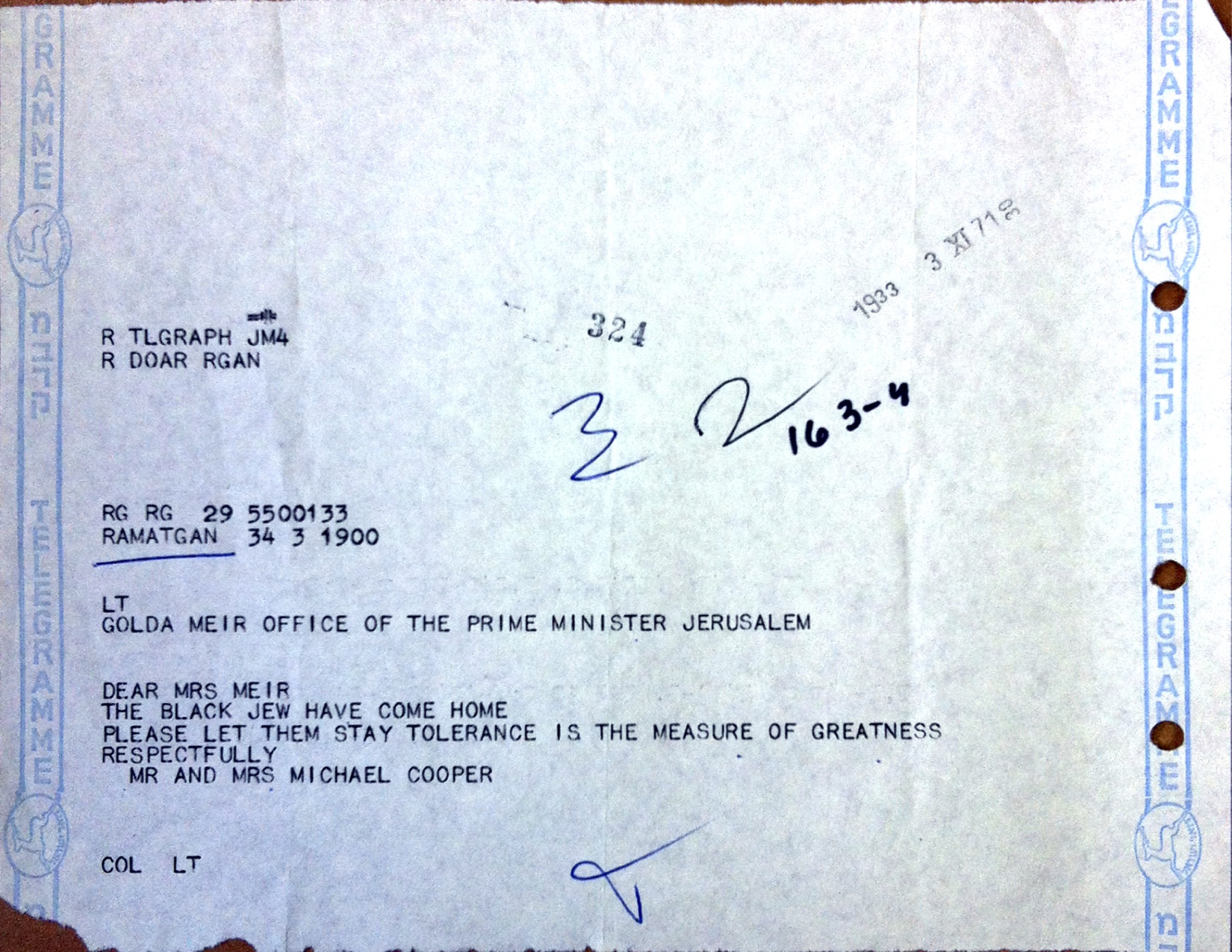

As we know from the archives, many people did speak out by writing directly to Golda Meir. On his website, Sheen speculates that the state held onto the racist letters, specifically, because “they provide ideological support for the government’s anti-African policies.” I’m inclined to think that the explanation is more mundane: open governments save documents, including personal letters to heads of state, and hold them in national archives for researchers to analyze. The fact that the government kept letters expressing support as well as contempt for the Hebrews (and black people in general) suggests that the decision to save the letters was not driven by a particular political agenda.

One final note: The treatment of African refugees in Israel today is deplorable. But, as I see it, their case is fundamentally different from that of the Hebrews. The latter left the U.S. of their own volition and demanded that Israel give them citizenship as the “true inheritors” of the land. They were not refugees, and they were not Jews, so Israel had no obligation to absorb them. By contrast, the approximately 50,000 African migrants in Israel today fled genocide, forced conscription, and/or economic deprivation in their home countries (Eritrea and Sudan, primarily). Most of them are refugees, according to the U.N., and should be protected by Israel rather than demonized and jailed.

3 Responses

Todah, very interesting.

Todah for sharing this! Interesting indeed!

Shalom Shalom

To all who have read this article; I pray you not be a reactionary but refer your analysis to the prophetic scriptures that declare that the Law shall go forth from Zion and the Word of Yahwah from Jerusalem.

If you have studied the history of the Promised Land; you certainly will come to the conclusion that the Holy Land is not a place for people who do not seek to be Holy should desire to immigrate and live; which has no bearing on the color of the would be citizens of Israel. Historically God has been the protector of the Israelites or Hebrews. There is no protection from the Creator without exemplifying a life style rooted in truth and righteousness.